Light flickering in the Autumn Dark

When the October sky over Somerset turns a bruised purple and the moon hangs low, the village streets spring to life with a glow that feels both ancient and mischievous. Children clutch glowing carved lanterns, their faces lit by flickering candles, while the air fills with a chant that has echoed through the countryside for generations:

“It’s Punkie Night tonight… Give us a candle, give us a light…”

This eerie procession, known as Punkie Night, is more than a quirky local festival; it is a living link to centuries-old customs that once guided lost souls, kept wandering malevolent spirits at bay, and turned the darkness of early winter into a community celebration. Here we’ll uncover the origins of the “punkie” lantern, trace the folklore from 19th‑century Somerset to the Celtic “Púca Night,” and explore how this regional tradition mirrors the modern Halloween rituals we know today.

What Exactly is Punkie Night?

Punkie Night is a lantern festival peculiar to Somerset, celebrated in villages such as Hinton St George. It takes place on the last Thursday of October every year.

The word “punkie” in Punkie Night originates from a local name for a lantern, with possible connections to “pumpkin,” “punky” (a term for a young child’s ghost), or the Old English word “punk” (timber or tinder).

On Punkie Night, local people carve glowing lanterns from ‘mangelwurzels’, a type of large beetroot grown for cattle feed. Once carved and lit from within by candles, these ‘punkies’ are carried through the street by children and adults alike, often wearing costumes. Traditionally, the punkies are borne through the streets or door to door in a noisy parade, where those carrying them call for treats or candles to light their lanterns, singing:

“It’s Punkie Night tonight,

It’s Punkie Night tonight,

Give us a candle, give us a light,

If you don’t, you’ll get a fright.

It’s Punkie Night tonight,

It’s Punkie Night tonight,

Adam and Eve wouldn’t believe,

It’s Punkie Night tonight.”

Iona Opie and Peter Opie described this Somerset custom beautifully in The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (Oxford University Press, 1987):

“To children in south Somerset a punkie is a home-made mangel-wurzel lantern of more artistic manufacture than those commonly made elsewhere for Hallowe’en. Laboriously executed designs, or floral patterns, or even scenes with houses, horses, dogs, or ships, are cut on the surface of the mangels, so that when the flesh has been carefully scooped out—leaving just a quarter of an inch to support the skin—and the stump of a candle has been lighted within, the designs become transparencies, and the lanterns ‘glow in the dark with a warm golden light’. These lanterns (reported from Long Sutton and Hinton St. George) are carried by a loop of string secured through two holes near the top just beneath the lid of the lantern. At Hinton St. George, where Punkie Night is the fourth Thursday in October, some sixty children come out into the street with their lanterns, and parade through the village in rival bands, calling at houses and singing.”

A Tale of Lost Men and Heroic Wives

According to local lore, Punkie Night can be traced back to when a group of Hinton St George men ventured to the nearby Chiselborough Fair in the early 1800s. The men spent their time at the fair drinking and carousing, and when they tried to return home after night fell, they soon lost their way. Although their village was only a few miles away, they became lost in the darkness without lanterns to light their path and were unable to find their way home.

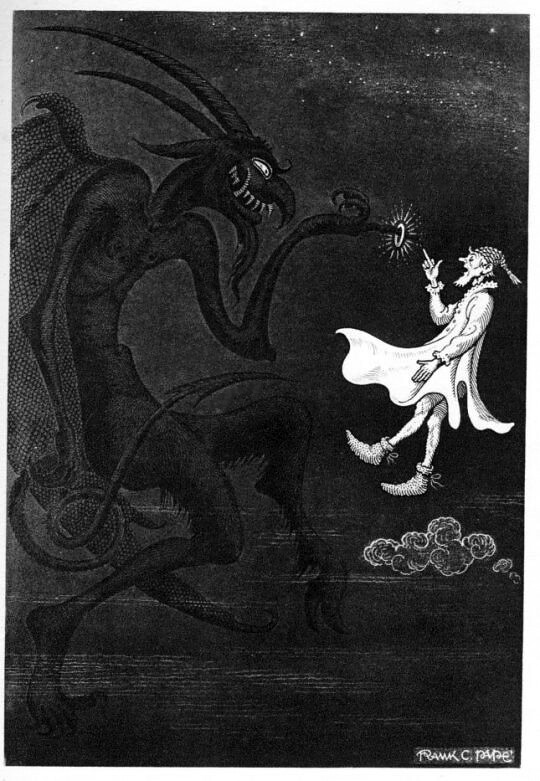

Their wives back in Hinton St George were distraught with worry and carved makeshift lanterns from mangelwurzels and took to the streets in search of their wayward husbands. Some say that when the men first spotted the light from the women’s lanterns glowing in the darkness, they mistook them for will o’ the wisps, or even restless spirits, and ran away in terror. Once they realised the flickering punkies were held by their heroic wives, they were soon guided home to safety.

Older Roots of Punkie Night and Shared Traditions

Punkie Night was first recorded in the 19th Century but may have much older roots. In Ireland, there is a Celtic celebration called “Púca Night” which has Otherworldly connections. Here, Púca refers to fairies and sprites, which were not necessarily clearly delineated ideas from ghosts and spirits in Irish folklore. Similar to Samhain, Halloween, and Punkie Night, the veil between the world of the living and the dead is believed to thin at this time. Lanterns were said to guide lost souls back to their homes and also ward off the spirits of the dead who would roam the land of the living during this liminal period.

In these traditions, there is also the shared custom of children and adults going door to door ‘souling’ to ask for something. In Púca Night and Halloween, children ask for sweets and candy, and on Punkie Night, a candle for their punkie was requested.

Both Punkie Night and Halloween also feature chanting or singing to request these gifts. In Punkie Night, children sing their traditional Punkie Night song, while modern trick or treaters might chant the popular naughty rhyme:

“Trick or treat,

Smell my feet,

Give me something good to eat!

If you don’t, I don’t care –

I’ll pull down your underwear!”

The carving of faces in punkies also has similarities to the customs of Samhain and modern Halloween. Scary faces were carved into turnip lanterns on Samhain and were placed in windows or carried outside to deter evil spirits. This has been adopted into modern Halloween traditions with carved pumpkin jack-o-lanterns being placed on window sills and on doorsteps.

These celebrations all incorporated themes of darkness, spirits of the dead, and the turning of the year. They belong to the season when the nights draw in, the harvest has ended, and people once believed that the dead and otherworldly spirits walked the earth. In this respect, Punkie Night can be seen as a regional English counterpart to Púca Night, Samhain, and Halloween. It is a survival of the same autumnal fears, folklore, and festivities that people experience at this time of year, but shaped by Somerset’s rhythms and spirit.

Why Punkie Night Endures

Punkie Night endures, weaving together folklore, community, and the timeless human fascination with light in the dark. From the crude lanterns carved by anxious wives in the 1800s to the elaborate mangelwurzel “punkies” paraded by today’s children, the festival captures a uniquely Somerset spirit while reflecting broader autumnal rites such as Samhain, Púca Night, and contemporary trick‑or‑treating. By preserving this tradition, the village of Hinton St George keep alive a story that celebrates resilience, imagination, and the comforting glow of shared history, proving that even as the nights grow longer, the light of community burns ever brighter.

Reference list

- Archive.org. (2025). Somerset in particular. [online] Available at: https://web.archive.org/web/20081020151750/http://www.england-in-particular.info/gazetteer/gz-somer.html [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

- Hole, C. (1976). British Folk Customs. Book Club Associates.

- Information-britain.co.uk. (2025). British Folk Customs, Punkie Night, Somerset. [online] Available at: https://information-britain.co.uk/customdetail.php?id=64 [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

- Maybury, K. (2024). The Mythology of Punkie Night. [online] The York Historian. Available at: https://theyorkhistorian.com/2024/03/04/the-mythology-of-punkie-night/ [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

- Moon Mausoleum. (2024). Halloween Stories: Punkie Night, A Spooky Tradition of Somerset’s Dark Past – Moon Mausoleum. [online] Available at: https://moonmausoleum.com/halloween-stories-punkie-night-a-spooky-tradition-of-somersets-dark-past/ [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

- Norman, M. and Books, N.T. (2025). Britain’s Folklore Year (National Trust). National Trust Books.

- Opie, I. and Opie, P. (1987). The The lore and language of schoolchildren Lore and language of school children. [online] Oxford University Press. Available at: https://archive.org/details/lorelanguageof00opie [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

- Pascal Tréguer (2020). ‘punkie (lantern)’ | ‘punkie night’. [online] word histories. Available at: https://wordhistories.net/2020/10/09/punkie-lantern-punkie-night/ [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].

- Roud, S. (2008). The English year : a month-by-month guide to the nation’s customs and festivals, from May Day to Mischief Night. London: Penguin Books.

- Wikipedia Contributors (n.d.). Punkie Night. [online] Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Punkie_Night [Accessed 29 Oct. 2025].